Anyway, he made an interesting point and I feel as though I need to respond. Here is the comment:

"This is terrific stuff!I suspect there's a certain amount of extrapolation in that music sample, even granted that the modal system makes it possible to guess how the rest ran.Every ancient music sample I've ever heard goes for something sombre, yet based on random comments from ancient sources, most Greek music must have been bouncy for dancing. This is the highbrow stuff, like the ancient equivalent of opera!"

Besides being completely FLATTERED that he thinks my "stuff" is "terrific", I am also COMPELLED to explain why the majority of music that survived and can be performed with some degree of accuracy is of a somber, ceremonial nature and not the dancy fancy music that many Greek writers and artists depicted. (Know that some of this is my own conjecture, not fact)

First and foremost: Music in ancient Greece was most often improvisational in nature and that is how musicians were trained to perform it. In case you don't know what that means, improvising meant making it up on the spot and mixing and matching it to fit the event that it was supposed to accompany. A wild orgy-tastic dance party would require a different sort of music than music performed simply to accompany a lavish banquet or entertain an important personage.

As you can imagine, this music was NOT written down. And if it was, whatever it was written on was probably not meant to last. Music like that did not have to ever be performed twice.

What music that we HAVE uncovered, particularly the oldest of songs and fragments of songs, were either carved into stone or stored in such a way that it would last and someone could pick up the music and perform it exactly as it was written.

For example, the song featured in my guest post (A fragment of a chorus from Euripides' Orestes) was written on parchment. I am not sure if I am correct in this, but I think the fact it was written on partchment is pretty significant and the fact that it was written down at all is even more significant. Regardless, it is obvious that Euripides wanted the song performed the same way for every performance. Also, because the song involved multiple performers, it was probably a fast(er) way for everyone to know what to sing or play.

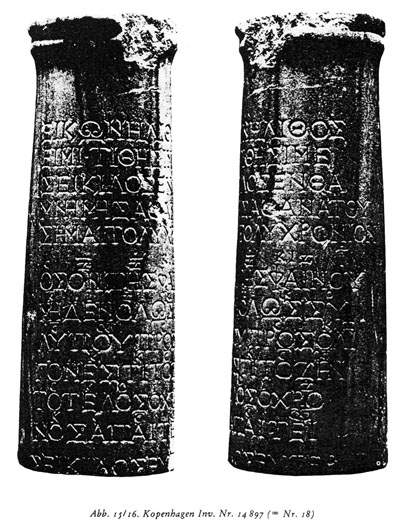

One other famous example is the Song of Seikilos (pictured above), actually one of the only songs that we have found completely intact. This song was carved into stone in Seikilos' wife's grave which is probably the only reason it has survived.

Both of these were songs that were MEANT to stand the test of time, whether for repeated performance or as a rememberance to a loved one. Since this performance was of a pretty depressing drama and the song came from a grave, both were understandably somber and sad. The majority of other songs that we have found are of the same ilk so that is why the majority of songs we can perform with any accuracy are these types of songs.

Here this song is probably pretty accurate. And a little more upbeat!

Sappho's Wedding Hymn

Excellent post, Karen!! I will put up a link to it from my blog tomorrow if you want :)

ReplyDeleteYes, please! :)

ReplyDeleteDone :D

ReplyDeleteI never thought my comment could be so inspirational! Thanks for writing more.

ReplyDeleteI like your logic that only serious music was likely to be written. The rarity about anything written on parchment is that it survived at all. Since writing was only relatively new, I imagine virtually all the folk songs and religious music predated any ability to record it. Have you read The Praise Singer by Mary Renault? At one point she has Simonides railing against bards who write down their work.

Your point on the improv must surely be true. I'd guess too that the flute girls doing the symposia party circuit must have had a repetoire of old favourites, like cover bands today.

mypopsox

ReplyDelete